Many people wonder if and how fats burn down during exercise – in other words, whether a workout actually breaks down stored fat. The answer involves understanding how the body stores energy and uses it during activity. In simple terms, body fat is a dense energy reserve, but it doesn’t literally “burn down” like wood. Instead, exercise triggers a series of biochemical processes that break down fat molecules so muscles can use them for fuel. In this article we’ll explore how fat is stored, how the body decides to use it during workouts, and what the terms “fat breakdown” and “fat-burning zone” really mean. Along the way, we’ll clarify common myths (for example, the idea of a single fat-burning workout zone) and highlight what science says about optimizing fat metabolism through exercise and diet.

Fats as Energy: How the Body Stores Fuel

Dietary fats and carbohydrates both provide energy, but fat is an especially concentrated fuel. In fact, fat stores about 9 calories per gram, which is more than twice the energy density of carbohydrates (about 4 calories/gram). This efficiency makes fat ideal for long-term energy storage. When you consume more calories than you immediately burn, your body converts the excess into triglycerides (three fatty acids attached to a glycerol molecule) that are stored in fat cells (adipocytes) under your skin and around organs. A lean adult can carry on the order of 100,000–130,000 Calories of fat stored in these cells which is enough to power the body for many days if needed.

Because fat is such a rich fuel reserve, the body carefully regulates when to tap into it. Under normal resting conditions, a mix of fuels (including blood sugar, stored carbs, and some fat) provides energy for essential functions. When you begin exercising, your muscles need extra energy. Initially the body uses readily available muscle glycogen and blood glucose. However, as exercise continues – especially beyond the first few minutes – the body shifts to mobilizing its fat stores for fuel.

This process starts in the fat cells. When muscle activity signals higher energy demand, hormones like adrenaline (epinephrine) rise in your blood. These hormones bind to fat cells and trigger lipolysis – literally “fat splitting” – which breaks each stored triglyceride into one glycerol and three free fatty acids. In other words, your body causes fats to break down into smaller components that can be released into the bloodstream. After lipolysis, those fatty acids travel through the blood, carried by proteins (such as albumin), and become available to working muscles as fuel. As each fat cell empties its fatty acids, the cell shrinks; you do not literally “lose” fat cells, but rather, you empty out their stored fats.

In summary, fat is stored primarily as triglycerides in adipose tissue, and it yields lots of energy. Through hormonal signals (like adrenaline) during exercise, the body induces fat breakdown (lipolysis), freeing fatty acids that can be burned for energy. Next, we’ll see how exactly muscles use those fats during different types of exercise.

Exercise and Fuel: When Muscles Use Fat

During any aerobic (oxygen-requiring) exercise, both carbohydrates and fats can provide the needed energy. The exact mix depends largely on exercise intensity and duration. At low exercise intensities (for example, slow walking or light cycling), fat is the dominant fuel. Sports scientists note that at very low power outputs (below about 40% of a person’s maximum aerobic capacity), fats supply most of the energy. As intensity increases to a moderate level (roughly 40–65% of maximum effort), the body splits energy about half-and-half between fat and carbohydrates. In fact, research shows that maximal fat oxidation – the point where fat contributes most to the fuel mix – occurs around moderate intensity (about 60–65% of maximum capacity).

At higher exercise intensities (such as sprinting or very strenuous interval training), carbohydrate becomes the main fuel. Above 70–75% of maximal effort, muscles rely much more on glucose and stored glycogen and far less on fat. This happens for several reasons: fast high-intensity exercise demands quick energy that carbs can provide, and blood flow is prioritized to active muscles (reducing fatty acid delivery from fat tissue). In practical terms, if you are pushing yourself near your limit, you burn a lot of calories but mostly from carbs.

However, this does not mean that fat is not used at all during hard workouts. Even in those cases, a portion of energy (via fatty acids from the blood and from intramuscular fat droplets) is still used. In fact, studies have shown that during moderate exercise a substantial share of the fatty acids delivered to muscle (about 80%) are actually oxidized to fuel exercise. Those fatty acids may come from fat cells (mobilized into the blood) or from tiny fat stores already within muscle fibers.

READ ALSO: Unlock Your Fat-Burning Potential: The Ultimate Guide to Heart Rate Zone Training

One helpful way to see this in everyday terms is to consider what happens in a workout. In the first several minutes of exercise, your muscles mainly use quick carbs. But if you keep going at a steady pace, your body gradually shifts more of the workload to burning fat. Research has found that roughly after 30–60 minutes of steady aerobic exercise, a larger portion of the energy comes from fat. (Of course, this also depends on how intense the exercise is – if you stay at a moderate pace it takes less time; if you are really just moderately active it may take longer.)

Crucially, fat burning during a workout is not an all-or-nothing switch. Even at low intensity, the body still uses some carbohydrate; even at high intensity, some fat is used. What changes is the percentage contribution of each fuel. In plain language: longer or sustained moderate activity tends to use a higher percentage of fat, whereas very intense bursts favor carbs. Nonetheless, exercise of almost any kind will use a combination of both fuels to meet energy needs. In all cases, the fats that are used must first be broken down via lipolysis as described above, then transported into muscle cells and their mitochondria (the “power plants”) for final burning.

Lipolysis: The Science of Fat Breakdown

Now let’s dive into what actually happens inside your body when fats are used during a workout. As mentioned, stored fat (triglycerides) must be split into free fatty acids (FFAs) and glycerol before anything can happen. This is the process called lipolysis. Hormones like adrenaline and low insulin levels during exercise activate an enzyme called hormone-sensitive lipase, which catalyzes this breakdown. In the words of exercise scientists, “By lipolysis, each molecule of triacylglycerol splits into glycerol and three fatty acids”.

Once split free, the fatty acids and glycerol exit the fat cell and enter the blood. Because fats are not water-soluble, they hitch a ride on proteins (albumin) in the blood until they reach working muscles. As you exercise and blood flow to muscles increases, more and more fatty acids are delivered to the cells that need fuel. This is why even though fat cells release fat, the actual burning happens inside the muscles.

Within muscle cells, each fatty acid must be transported into the mitochondria for combustion. This involves a special transport system (the carnitine shuttle) but the key point is that in the mitochondria the fatty acid chains go through a sequence of reactions (beta-oxidation followed by the citric acid cycle and electron transport chain) to release energy. In essence, every carbon in the fatty acid is eventually converted to CO₂ and water, releasing energy (ATP) in the process. You can think of the mitochondrion as the cell’s “fat-burning furnace”; it is the only place in the body where a triglyceride is completely broken down to generate usable energy.

So what does “fat breakdown” mean in practice? It means that during a workout your body chemically dismantles fat molecules so muscles can use them. Importantly, fat doesn’t literally combust in the body – it gets oxidized. As one expert explains, because fat is a carbon-based fuel, burning it is like burning charcoal – the end products are carbon dioxide and water. In fact, the carbon atoms in fat are released as CO₂ (exhaled with your breath) and the hydrogen becomes water (sweat, urine, or other routes). All the while, energy is liberated for your muscles to contract.

It’s worth emphasizing that fat must be broken down before it is burned. In everyday terms, you cannot “burn fat” directly inside a fat cell – first you must release it as FFAs. Only then can it be taken up by muscle. An analogy is thinking of a fat cell like a storage tank full of oil; exercise drills a tap that lets the oil flow out (lipolysis), and the muscles then use that oil. If no energy is needed (or if you keep eating as much as you burn), the tank stays full. Only when energy demand exceeds supply (for example, during prolonged exercise or a calorie deficit) does the tank get tapped and the fat cell empties out.

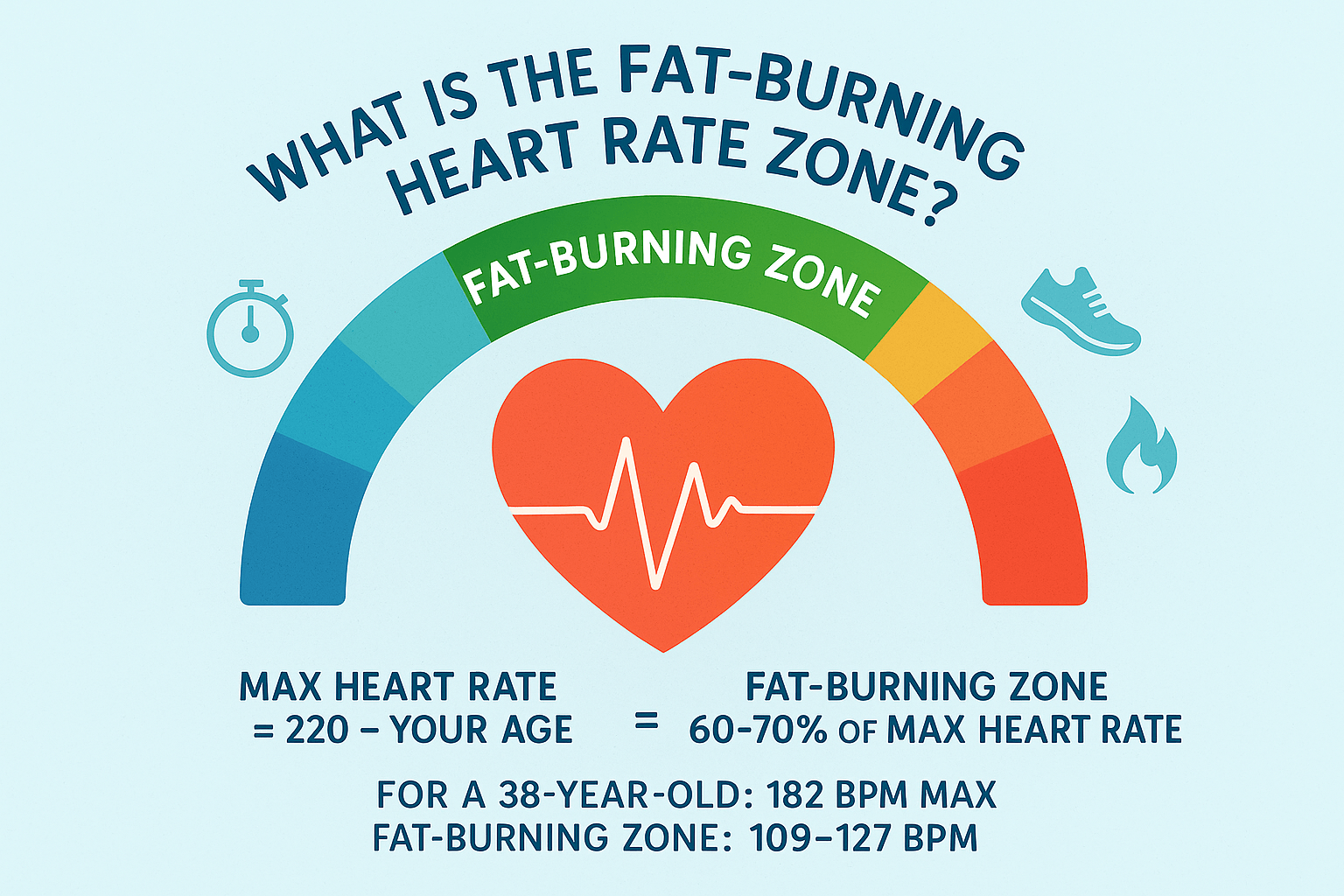

Intensity and the “Fat-Burning Zone” Myth

A common question is whether certain workouts burn more fat than others. For example, many people have heard of a so-called “fat-burning zone”, typically described as exercising at about 60–70% of maximum heart rate. The idea is that this zone supposedly makes your body burn proportionally more fat. The truth is more nuanced. It is accurate that at moderate intensity the body uses a higher percentage of fat than it does at high intensity. In other words, if you pedal on a stationary bike at an easy pace, a larger share of your calories come from fat. But at high intensity, although fat contributes a smaller share of the fuel mix, you burn overall more calories (mostly from carbs) in the same time.

Scientific studies have clarified this with some precision. Researchers found that maximal fat utilization tends to occur at moderate efforts (roughly 60% of maximum aerobic capacity). If you push much harder (say sprinting near 85–90% effort), fat use drops significantly and carbohydrates take over. Conversely, if you go very easy, total calorie burn is lower, so the absolute amount of fat used may also be relatively modest.

In practice, this means that doing a longer moderate-intensity workout can burn a good amount of fat calories both during the workout and over time. At the same time, high-intensity interval training (HIIT) can accelerate overall fat loss too – not necessarily because each sprint burns more fat in that moment, but because the total energy expenditure is higher and it drives metabolic adaptations. Indeed, a tougher workout can trigger more post-exercise fat burning. For instance, intense strength or interval workouts raise your excess post-exercise oxygen consumption (EPOC), sometimes called the “afterburn” effect. After such workouts, your body continues to burn calories (partly from fat) as it recovers. One fitness guide notes that lifting weights at high intensity increases the calories you burn after the workout, boosting overall fat breakdown. In short, you burn more total fuel – and thus more fat overall – by working harder, even if the immediate fuel mix is different.

Another way exercise aids fat loss is by involving more breathing. Since fat oxidation produces a lot of CO₂, breathing hard during exercise simply helps expel that CO₂. The Cleveland Clinic points out that exercise speeds up fat metabolism in part because it makes you breathe more, which removes carbon dioxide (a byproduct of fat burning) from the body faster. (Remember: those extra breaths during exercise are literally helping blow fat out of your lungs!)

All this means: there is no magical single heart-rate or intensity that only burns fat. Whether you walk briskly, jog, cycle, or lift weights, you will burn some fat along the way. Higher intensity workouts burn more total calories (helping with fat loss indirectly) and also trigger ongoing fat metabolism, while moderate workouts burn a higher percentage of fat during the session. A balanced routine that includes both kinds is often recommended. The key for lasting fat loss is consistency and total energy balance, not just hitting a “fat-burning” number.

Maximizing Fat Metabolism: Training and Lifestyle Tips

Knowing how fat breakdown works can help you plan your workouts and lifestyle. First and foremost, remember that fat loss requires an energy deficit: you must burn more calories than you consume for your body to dip into its fat stores. As one expert explains, when you take in fewer calories than you burn in a day, “your body turns to its fat reserves… for energy”. Exercise provides part of that increased calorie burn. However, diet is typically the bigger factor; without a caloric deficit, you won’t lose fat no matter how much you exercise.

That said, regular exercise has many beneficial effects on fat metabolism. Over weeks and months of training, your body adapts to become better at burning fat. For example, consistent aerobic training makes you more efficient at taking up and using oxygen. In practical terms, this means your muscles become better at using oxygen to oxidize fat. Exercise also improves blood flow and circulation of fatty acids: active muscles get greater blood supply, so fatty acids move more easily from storage into working muscles. Additionally, trained muscles grow more mitochondria (the cellular power plants) to handle energy production. All these adaptations let your body break down and use fats more readily over time.

Building muscle through resistance training is another smart strategy. Muscle tissue itself is metabolically active – it burns calories even at rest. So more muscle means a higher resting metabolic rate. In fact, research and fitness guidance emphasize that lifting weights helps preserve and even increase metabolism. A diet-only approach to weight loss can slow your metabolism by up to ~20%, but keeping or building muscle prevents that slowdown. High-intensity strength workouts also create an afterburn effect similar to cardio; you continue burning calories (and fat) after you finish lifting. In other words, by strengthening muscle you make your body a better fat-burning machine around the clock.

Finally, bear in mind that the fat “breakdown” process also produces heat. Some of the energy from fat combustion is released as heat (that’s one reason you feel warm during exercise). Keeping your workouts safe and ensuring proper nutrition and hydration is important for supporting these metabolic processes.

In summary, yes – your body does break down and use fats during exercise, but only in proportion to your energy needs and the conditions of the workout. Fats must first be liberated from fat cells and then oxidized in muscles. A balanced exercise program (including both aerobic and strength components) combined with a sensible diet is the most effective way to ensure those fat reserves are gradually reduced. In practical terms, think of a workout as one way to create energy demand; your body responds by breaking down fats (and carbs) to meet that demand. Over time, repeated workouts make your metabolism more efficient at using fat, helping you “burn” (break down) more fat even outside the gym.

Key Takeaways:

- Stored fat is used during exercise through a process of fat breakdown (lipolysis) triggered by exercise hormones.

- Muscles then oxidize those freed fatty acids (with oxygen) for energy. Low-to-moderate intensity workouts tend to use a higher percentage of fat as fuel, but intense workouts burn more total calories (and also enhance post-exercise fat burning).

- Consistent training improves the body’s ability to use fat, and building muscle raises resting metabolism. Throughout any calorie deficit, the body must ultimately convert fat to CO₂ and water – mostly exhaled – to lose fat mass. Understanding these details can help you plan workouts and nutrition for effective fat loss.